Touring Plays

Pizarro

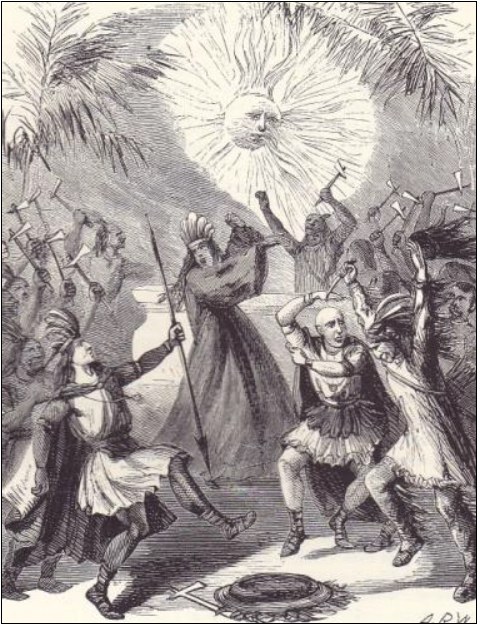

Pizarro – Indian War Dance in the Temple of the Sun

Solomon Smith: Theatrical Management in the West and South for Thirty Years

The plot of the play Pizarro is taken from the tragic death of Atahuallpa, the 13th and last emperor of the Incas, who died by strangulation at the hands of Francisco Pizarro’s marked the end of 300 years of Inca civilization.

Touring Pizarro

To tour a production like Pizarro in the early nineteenth century took ingenuity and fortitude, particularly for a small company like the Vaughan troupe. On the large stages of the established theatres in London and New York, Pizarro was a lavish production featuring a large cast, spectacular scenery and vivid dramatic action. How would a small colonial company like Vaughan’s adjust the play to tiny stages, limited scenery and a small group of actors? For a general idea of how many of these small touring troupes adjusted to the size of various stages it is useful to read Sol Smith’s description of how Sam Drake’s company of six actors gave a performance of Pizarro in St. Louis, Missouri in 1820 using a stage area ten feet wide and eight feet in depth with cast members playing more than one role. One of Drake’s cast members actually played six roles for a salary of six dollars per week. In his book Theatrical Management in the West and South for Thirty Years Smith says,

For my own part, I was the Spanish army entire! But my services were not confined to that party. Between whiles I had to officiate as High Priest of the Sun; then lose both of my eyes, and feel my way, guided by a little boy, through the heat of the battle, to tell the audience what was going on behind the scenes; afterward, my sight being restored and my black cloak dropped, I was placed as a sentinel over Alonso! Besides, I was obliged to find the sleeping child, fight a blow or two with Rolla, fire off three guns at him while crossing a bridge, beat the alarm drum, and do at least two thirds of the shouting! Some may think my situation was no sinecure; but, being a novice, all my exertions were nothing in comparison with those of the Drakes, particularly Sam, who frequently played two or three parts in one play, and after being killed in the last scene, was obliged to fall far enough off the stage to play slow music as the curtain descended!

Our stage was ten feet wide and eight feet deep. When we played pieces that required bridges and mountains, we had not much room to spare; indeed, I might say we were somewhat crowded.

Because these early touring troupes travelled by horse-drawn wagon, they carried a minimum of scenery, props and costumes. When they arrived at their performance destination they had to do their best to fit their scenery to the available stage area.

Marilyn Castro’s book, Actors, Audiences, & Historic Theaters of Kentucky gives fine descriptions of the stage equipment carried by any early nineteenth century touring company. It usually consisted of a painted drapery proscenium, a baize, drop curtains and structural wings. The proscenium curtain and baize were suspended between two walls and when the baize was opened, it defined the stage area. This was especially necessary when performing in spaces where there was no stage, such as the Burlington Hotel in Hamilton. The baize or front curtain was made from a soft green woollen fabric. Once it was opened at the beginning of the performance, it remained so until the conclusion. This was considered somewhat of an entertainment plus for the audience as they watched scenery changes carried out by the actors between performance segments.

Backdrop scenes were painted on fabric attached to rollers. Standard scene drops of the era included a street, parlour, kitchen, palace, a garden, and a small wooded landscape. Structural wings were flat rectangular boards covered with painted canvas. The standard number of wings, space permitting, was three on each side of the stage area, and their purpose was to provide stage entrances and exits for the actors. Painted to coordinate with the scenes on the backdrop, these structural wings depicted such things as doors, windows, gardens, etc., and were intended to bring a vague impression of perspective to the scenery. It seems obvious that early nineteenth century audiences were expected to use a great deal of imagination, since the number of backdrop scenes and wings would vary according to the size of the performance area, and the financial status of the troupe.

Irishman in London or, The Happy Negro

Irishman in London or, The Happy Negro was a popular vehicle on both sides of the Atlantic. It was first performed at the John Street Theatre in New York City in June of 1793. Although a farce, it is essentially a commentary on the increasing immigration of the Irish and Africans into London, England at the period. London was the metropolitan center of England, and consequently anyone who was foreign was considered fair game for trickery. In the play Irish and African servants are comically compared.

As an aside it is interesting to note that prior to the play’s debut in London, the censor John Larpent took exception to some of the dialogue directed at one of the black characters. Consequently he put the blue pencil to the offensive text.

Reading Guide

Reading Guide

Castro, Marilyn. Actors, Audiences, and Historic Theaters of Kentucky (Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000)