Sallie St. Clair, Danseuse

Hamilton’s introduction to the Romantic Ballet Repertory – 1847

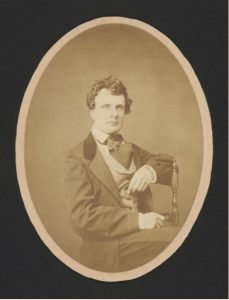

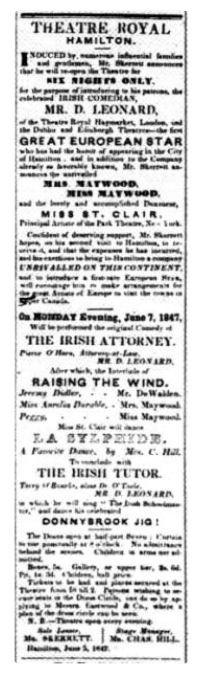

When Sallie St. Clair danced her solo from the ballet, La Sylphide on the stage of Hamilton’s Theatre Royal in June 1847, she was a member of George and Emma Skerretts touring company. As a young lady of sixteen years of age noted for her grace and beauty, she was also an experienced professional ballet dancer with a working knowledge of the Romantic Ballet repertory. Born in 1831, she was brought to the United States from England as an infant and made her first appearance on stage at the Park Theatre in New York City as a child danseuse. Sallie is something of a phenomenon in the history of ballet in nineteenth century America, because she was one of a small group of dancers who received their entire ballet training in the United States.

The majority of this ballet training was most likely taken under the direction of Paul H. Hazard in Philadelphia. In 1835 Hazard and his wife who had been members of the Paris Opera settled in Philadelphia and opened their ballet school there in one of the most fashionable public spaces in the city, the Assembly Buildings on the southwest corner of Chestnut and 10th Streets. It was one of the first ballet schools in the United States and because dancers trained by Hazard were superior to those trained in New York City (which was already the country’s artistic capital,) European itinerant stars in search of supplementary dancers for their own performances were eager to hire them.

Marie Taglioni as the Sylph in the ballet La Sylphide c.1832. Illustrates the type of ballet shoes (pointe shoes) and costume probably worn by Sallie St. Clair when she danced her solo from the same ballet in Hamilton in 1847. Courtesy of English Wikipedia

Sallie’s knowledge of the Romantic Ballet repertory was probably first acquired from Hazard, and then enhanced considerable when she was performing as a member of Mlle. Augusta’s ballet company where she would have gained valuable professional training in both technique and repertory.

Mlle. Augusta, a native German, was born in Munich in 1806. Her ballet training was taken in Bavaria under the prestigious dancer, teacher and choreographer Filippo Taglioni, father of Maria Taglioni who was the most prominent ballerina of the Romantic Period. Before her successful career in America, Augusta had danced with the resident ballet company at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in London, England where she had made her debut in February of 1833 as a fairy in Sleeping Beauty. In 1846 she and her company gave the first performance of the ballet Giselle in New York City with Sallie St. Clair dancing the role of Olia.

In 1847 Sallie left the Augusta Troupe and toured the United States and Canada as a solo dance artist. Her first Canadian engagement was in Montreal in July of 1847 as a member of George and Emma Skerretts dramatic stock company as a between the acts performer.

Chestnut Street Assembly Building in Philadelphia where the Hazard Ballet School was located. Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion at the Free Public Library

The Skerretts had arrived in Montreal from New York City in the spring of 1845 where George took over the responsibilities as lessee and manager of the Royal Olympic Theatre. An industrial couple by 1847, the Skerretts had expanded their enterprise to include a small summer touring circuit that included theatres in Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton and Albany, New York, as well as the new Theatre Royal in Hay’s Market in Montreal.

While touring with the Skerretts during the summer of 1847, Sallie introduced audiences to dance excerpts from the current Romantic ballet repertory choreographed by some of the most prestigious choreographers of the Period. The choreographers and their works included in Sallie’s repertory were Filippo Taglioni (La Sylphide, La Fille Du Danube, Bayadere, and La Gitana), Jean Coralli/Jules Perrot (Giselle), Jules Perrot (Esmeralda, Le Délire d’un peintre).

Mlle Augusta

“Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music,

The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University”

In June of 1848 Sallie returned to Montreal’s Theatre Royal again joining the Skerretts’ summer season as the featured between the acts performer. After completing her summer engagement with the Skerretts in mid-August, she joined the corps de ballet of the Monplaisir Ballet Company for their summer season at Montreal’s Theatre Royal.

Hippolyte Monplaisir and his wife Adele Monplaisir, leading dancers with the company, came to America with a solid background in classical ballet. They had studied under Carlo Blasis in Milan and had performed in many countries throughout Europe. Featured dancers at La Scala they had worked there with the renown ballerinas Marie Taglioni, Fanny Elssler, and with the great choreographer Jules Perrot. Sallie remained with the Monplaisirs to tour the United States as far south as New Orleans. (It is a possibility, though unsubstantiated that she toured as far west as California.)

Hippolyte Monplaisir and his wife Adele Monplaisir

“Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music,

The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University”

Completing her tour with the Monplaisir’s, Sallie went on to travel the United States as a solo dance artist and occasional actress. By 1852, at the age of twenty-one she was beginning her transition from dancer to melodramatic artist. She had made her acting debut in 1846 at the age of fifteen at the Museum Masonic Hall in Philadelphia in the role of Julia Dalton in Thomas Haynes Bayly’s one act burletta, One Hour; or The Carnival Ball. As well, while traveling the southern United States in 1852, as a member of the stock company associated with Bates’s Theatre she received complimentary reviews from the St. Louis Intelligencer. The critic mentioned that she had a fine talent for acting and should give up the ballet and pursue acting.

Why Sallie decided to pursue an acting career is unclear. Perhaps she was well aware that a dancer’s career is limited by age, in that the body sooner or later begins to wear down physically, making it difficult to perform the classic works, particularly those works which require dancing on pointe. Or, seeing the rise in popularity of the melodrama, she may have realized that not only was she suited for this type of role, but if she was successful she would gain stardom and a considerably enhanced financial income for a longer period of time than she would have had as a dancer.

The transition from dancer to melodramatic actress worked well for Sallie. Capitalizing on her dance background and experience, she quickly grasped the dominant characteristics of the melodrama: gesture, facial expressions, tableaus and music. In addition to her considerable talent she also had in her favor the fact that at the mid-nineteenth century women had begun to play a more prominent role in the development of theatrical entertainment. It was now becoming more sociably acceptable for women to take up a career in theatre. Historically, the theatre had been considered a male domain, and women associated with the theatre were viewed as unladylike, and were socially ostracized.

As the 1850s progressed so did Sallie’s reputation as a star of the melodrama, and her reviews were consistently favorable.

In August of 1858 Sallie returned to Hamilton appearing in the melodrama Jack Sheppard at the Royal Metropolitan Theatre where she suffered an unfortunate accident while on stage. The following article was published in the New York Clipper on August 21, 1858.

Miss Sallie St. Clair met with an accident at Hamilton, C.W. (Canada West) on the 6th inst. On the occasion of her benefit. The accident occurred in the last set of Jack Sheppard, Miss St. Clair was rapidly crossing the stage, when suddenly she tripped and fell heavily, striking her forehead on the floor. Dr. Case was in immediate attendance and every attention was paid to the sufferer, who, we are happy, to say, is now only suffering from the effects of the shock to her nervous system.

Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music,

The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University

During her Hamilton performances in addition to Jack Sheppard, Sallie appeared in the popular melodramas Lucretius Borgia and The French Spy. Completing her Hamilton engagements she then embarked on a tour of Southern Ontario and Quebec, after which she returned to the United States.

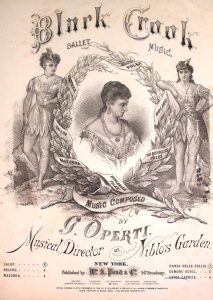

In 1860 Sallie married the writer/comedian and theatrical manager, Charles M. Barras author of the famous Black Crook. At this point in time Sallie was an established star of melodrama, playing all of major theatres in the United States, and Barras intended the Black Crook as a vehicle for her. However, Barras’ traditional melodramatic script was never produced, because William Wheatley, the manager-producer who was intending to mount the production at Niblo’s Gardens in New York City had serious doubts concerning the merits of the script. When he was presented with an alternative he quickly took it. This came in the form of a French ballet troupe which was scheduled to perform the Romantic ballet La Biche aux Bois in the Academy of Music.

Unfortunately, not long before they were to open the Academy burned down. Wheatley quickly stepped in and suggested to the producers Henry C. Jarrett and Harry Palmer that they combine forces with him to produce a grand musical extravaganza. Barras objected to the changes in his script but ultimately he accepted a down payment of $1500 and a royalty fee contract which over the years paid out handsomely and enabled him and Sallie to have a very comfortable lifestyle.

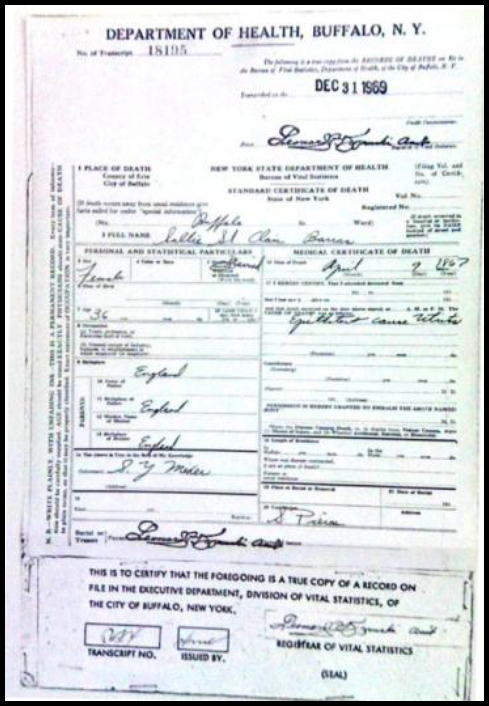

Sadly neither Sallie nor Charles lived long lives to enjoy their good fortune. Sallie died from a miscarriage at their home in Buffalo, New York in 1867 at the age of thirty-six. She is buried in Buffalo, New York. Charles passed away in 1873 at the age of forty-seven years as a result of a train accident.

Reading Guide

Anatole Chujoy. “Ballet in America.” The Dance Encyclopedia. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967. Print.

George C. Odell. Annals of the New York Stage. 2nd ed. V 5, New York: Columbia UP, 1927- 49. Print.

Hamilton Spectator. Hamilton Public Library, Local History and Archives. Hamilton, ON Canada. Microfilm.

Lillian Moore. Chronicles of the American Dance From the Shakers to Martha Graham, ed. Paul Magriel (New York, New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1978). Print.

Montreal Gazette, 16 June 1848. Microfilm.

Noah M. Ludlow. Dramatic Life As I Found It, (New York/London: Benjamin Blom, (1966). Print.

Sharon Steel. “Ballet.” Philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/

![The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) Apr 8, 1856 [First Edition]](http://www.stepsintime.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/news-238x300.jpg)