The Quadrille Band

Hamilton 1840 – 1860

Music in Hamilton at the mid-nineteenth century was an invaluable source of entertainment for both polite society and the city’s rapidly rising middle class. One of the most popular forms of musical entertainment was the Quadrille Band. The Quadrille Bands of the nineteenth century were established musical groups that provided the accompaniment for ballroom dancing and theatrical productions. As well, they offered the enjoyable experience of listening to popular music played by skilled musicians.

Hamilton at the mid-century had a population of ten thousand people, and at least six professional Quadrille Bands. Major Edward Kelk’s, Mr. Hallet’s, (later to become the Kelk/Hallet band,) Mr. Bain’s, The Hamilton Quadrille Band, the O’Neill and Steel’s Quadrille Band and the Zȍller Family Orchestra were all kept busy providing not only accompaniment for social dancing, musical soirees and concerts, but also filling the duties as pit band at the Theatre Royal.

The Royal’s pit band most likely followed the era’s tradition, in that it was a small to medium ensemble dominated by wind, brass and percussion, backed up by several stringed instruments. In the large metropolitan centers of North America, the bands tended to be more flexible and were composed of anywhere from two to twenty-five instruments including the harp. Further, the size of the band depended on the importance of the occasion, or the prominence of the theatre. Band members were expected to be skilled players and musically literate, i.e., proficient in reading music. Additionally they were expected to be dependable. It’s likely that the Royal’s band was a contract negotiated with the conductor, who then paid the musicians. This appears to be supported by the announcement published in a Hamilton Spectator advertisement dated November 8, 1848, stating that the Management Committee for the Hamilton Amateur Theatrical Society had engaged Mr. Hallet’s Quadrille Band for the season. If Hallet’s band had been a volunteer group, the term “engaged” would not have been used.

Conductor’s responsibilities

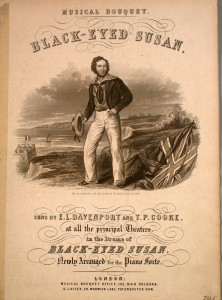

Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University

As the conductor of the pit band at Hamilton’s Theatre Royal, Mr. Hallet was a very busy man. His responsibilities included providing arrangements for all the music performed by the band, and on occasion he would also play with the ensemble. He adapted the music of visiting professional theatrical performers to suit their individual needs, and if necessary composed music for the performances of the Hamilton Amateur Theatrical Society. All incidental music, dance music, and songs were under his responsibility, as well as the popular music played between the acts and plays.

His talent in adapting and orchestrating was particularly valuable in the case of popular melodrama performances. Two outstanding examples performed by the Hamilton Amateur Theatrical Society were The Broken Sword by William Dimond, and Black Eyed Susan by Douglas William Jerrold. Like many melodramas, both pieces included a musical score written specifically for the drama. However, the director of a play could request changes in the score, and it would be the conductor’s responsibility to adapt it accordingly. (This was possible since at this time there were no copyright laws.) Even if the script did not include a musical score, it would require music cues, to indicate the stage action. Therefore the conductor would need to either compose, or find appropriate music and orchestrate it accordingly. It was the conductor’s responsibility to know when and how to use specific musical dynamics, by choosing the correct musical instruments for any musical drama. For example, tremolo is used extensively in melodrama to build dramatic intensity; ideal instruments for this are strings, flutes and some percussion instruments because they are able to play and sustain quiet dynamics over an extended time. Musical accompaniment was especially important to the melodrama, its primary role being to provide a firm emotional foundation for the drama.

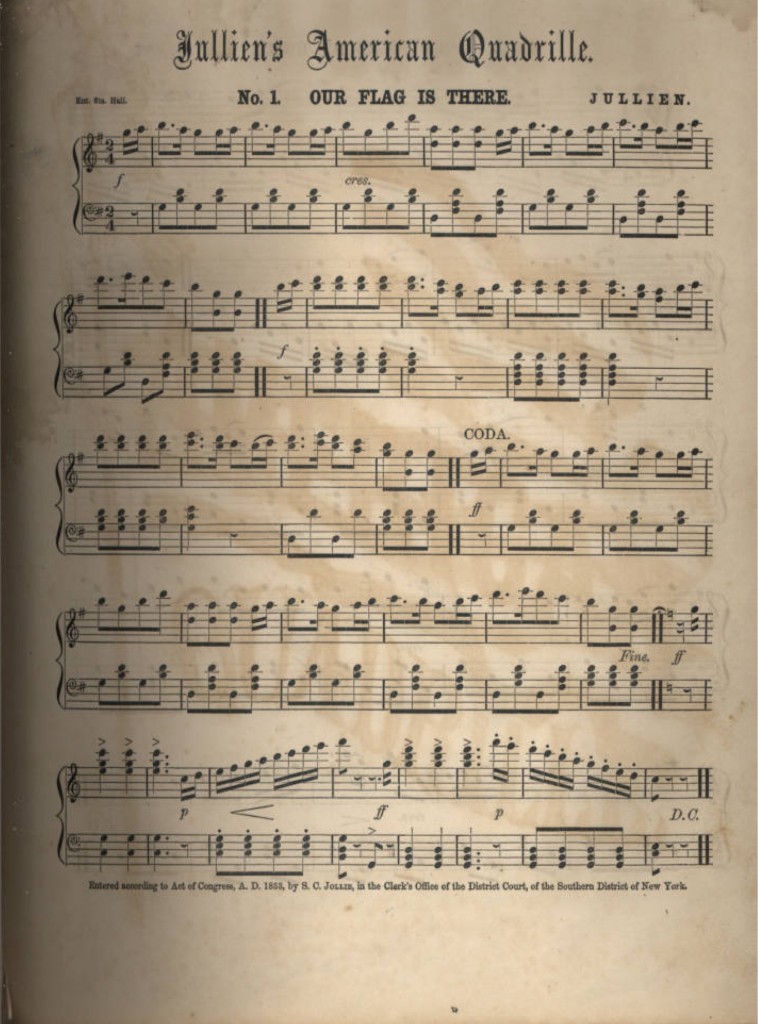

Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University

Conductor Hallet’s responsibilities in providing musical accompaniment for balls, dancing assemblies and private dance parties were just as extensive as his pit band duties. His first duty in providing music for such occasions was to meet with the floor manager of the ball or assembly; in the case of a private party, it would require a visit to the home of the hostess. In these meetings certain criteria would be discussed and agreed to. Foremost in the criteria would be that the band played each dance on the program in accordance with the way in which the piece was composed, meaning that tempo and repeated sections would be played as set down by the composer. Ballroom dancers were acutely aware of the music, particularly in the quadrille dances which were composed in various Figure Sets directly related to the music. Any deviation from the timing or the musical repeats would result in disorder on the dance floor and embarrassment to the dancers.

For example, if the polka was listed on the dance program then the conductor was to instruct his musicians to play with vitality, but not so enthusiastically that the dancers would lose their self-decorum. Instruction for the waltz stipulated that it was to be played tenderly and distinctly, laying the emphasis on the first note of each bar, which marked the timing clearly for the dancers. This enabled them to keep a regular pace with the music and to allow them to enjoy the beauty and effect of the dance.

Last, but by no means least, was the behavior of the musicians. This subject was stressed by hostesses of private parties. Under no circumstances were the musicians to associate with the party guests, nor were they to be offered any kind of alcoholic beverages or refreshments. Essentially they were in attendance to serve their employer, the hostess of the party whose social reputation in giving receptions was always under scrutiny by her friends, and her husband’s colleagues.

The life of mid-nineteenth century professional quadrille band musicians was not easy. The insecurity of not knowing when their next engagement would turn up, and frequently having their skills and behavior scrutinized must have been, at times, discouraging and even annoying. In the theatre, musicians were constantly observed by their conductor and the theatre’s manager, as well as egocentric dancers, singers, actresses and actors who could be incredibly demanding in their efforts to look good in front of the public.

Actually, their situation was not all that different from a twenty-first century professional musicians. As in everything it’s a case of half full or half empty; it takes a special kind of dedication to survive in any art.

Reading Guide

Elizabeth Aldrich. From the Ballroom to Hell: Grace and Folly in Nineteenth-Century Dance. (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991).

Elizabeth Aldrich. From the Ballroom to Hell: Grace and Folly in Nineteenth-Century Dance. (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991).

Rick Altman. Silent Film Sound. (Columbia University Press, 2004).

David Horn. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World 2:11.

Julian Mates. America’s Musical Stage: Two Hundred Years of Musical Theatre (Westport, CT, USA: Praeger Publishers, 1985).

Julian Mates. America’s Musical Stage: Two Hundred Years of Musical Theatre (Westport, CT, USA: Praeger Publishers, 1985).

Michael Pisani. Music for the Melodramatic Theatre in the Nineteenth Century London and New York (University of Iowa Press, 2014).

John Spitzer, Ed. American Orchestras in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, c2012).

https://theatremusic.wordpress.com/2012/04/17/underscoring/

A complete history of the Theatre Royal will appear in Freda’s forthcoming book, Window into another time: Theatre in Hamilton 1800 – 1850.